Fareed Zakaria (Source: CNN)

Fareed Zakaria’s Why They Hate Us, updated to include the Orlando massacre, has been playing on CNN again this weekend. It’s an excellent documentary by one of my favourite commentators. (The full 40 minute documentary is at the bottom of this post.)

Reza Aslan, who’s described throughout as a religious scholar, is included amongst the experts talking about the intersection between Islam and the West. This clip (which I have no argument with) is of one of his appearances on the show:

Apostasy

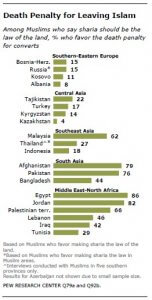

Following this clip, Zakaria goes on to outline some of the Pew Research Center statistics that I’ve presented here before such as that in Egypt more than 80% of those who want Sharia think adulterers and apostates should be killed.

Following this clip, Zakaria goes on to outline some of the Pew Research Center statistics that I’ve presented here before such as that in Egypt more than 80% of those who want Sharia think adulterers and apostates should be killed.

In relation to statistics like these, Aslan says:

I mean, we may be appalled by certain regressive beliefs, but they are just beliefs. The issue is people’s actions.

This has been a theme of Aslan’s before – that beliefs don’t matter. This is a claim of his I have dealt with at length previously. My opinion is that it’s ridiculous. In order for a person to act on a belief, they first have to have it. No one kills someone for apostasy if they don’t first believe that apostasy is something deserving of death.

Zakaria appears to share this view. He says:

But can some bad thoughts lead to bad actions?

He then goes on to point out Bill Maher’s statement on the subject on his show, Real Time, another comment I’ve used here before:

If vast numbers of Muslims across the world believe, and they do, that humans deserve to die for merely holding a different idea, or drawing a cartoon, or writing a book, or eloping with the wrong person, not only does the Muslim world have something in common with ISIS, it has too much in common with ISIS.

False Analogy: Westboro Baptist Church versus Islamists

Zakaria then provides Aslan’s response to Maher, which as well as being a false analogy, contradicts his statement above that beliefs are unimportant:

The Christians of the Westboro Baptist Church believe that God hates homosexuals, and so as a result of that belief they picket the burial ceremonies of American soldiers who die overseas. Now Christians in the United States also believe that homosexuality is a sin, so they share that belief with the Westboro Baptist Church. But they would never share in those actions. By Bill Maher’s logic, those two groups are essentially the same because they share one fundamental belief.

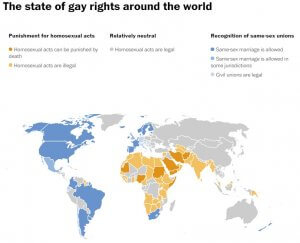

Aslan’s analysis doesn’t make sense to me. For a start, there is no logical relationship between the belief that God hates homosexuals and the picketing of the funerals of US soldiers killed overseas. Secondly, not all Christians in the United States believe that homosexuality is a sin. That leads to a third point – Maher never said “all” Muslims, but Aslan is responding as if he did. Most important of all though is that while the fact that the Westboro Baptist Church pickets funerals is extremely offensive, it pales in comparison to killing people for their sexuality, beliefs, or for adultery. And we’re not just talking about terrorists here – there are ten countries where homosexuality, for example, is punishable by death, all of which are Muslim majority.

State of Gay Rights Worldwide 2016 (Source: Washington Post)

Analogy: Mormonism versus Islam

Zakaria features a different and more accurate analogy – one which Sam Harris provides:

… have a play on Broadway like The Book of Mormon [which parodies the religion]. It is currently unthinkable to produce such a play on the topic of Islam. So what do the Mormons do in response to this play? They took out ads for Mormonism in the program, which is just an adorable response. … there is no-one who produced that play who lost any sleep over whether they might be killed, or hunted for the rest of their lives by crazy Mormons. And that is what we have to get to on the topic of Islam.

Zakaria, to his credit, agrees with Harris.

To be fair, Aslan later says something I do agree with:

One percent of the population of America is Muslim. Most Americans don’t know any Muslims. And so it becomes very easy when confronted with extreme acts of violence in the name of Islam, it becomes very easy to conflate that with mainstream, everyday, Islam. We would never make that mistake when we’re confronted with extreme acts of violence or radical interpretations of Christianity because we live in a country that’s seventy percent Christian. We are tribal ultimately. We’re much more likely to forgive the extremes within out own tribe that we are extremes in other people’s tribes.

I’ve written just that on several occasions. Perhaps he’s been reading Heather’s Homilies? 🙂

Full episode of ‘Why They Hate Us’:

If you enjoyed reading this, please consider donating a dollar or two to help keep the site going. Thank you.

Apropos of nothing, here are three paragraphs from the book I’ve just read, Theodore Zeldin’s An Intimate History of Humanity, about how different types of people try to cope with life and how that relates to human development through history. It is an odd but engaging book. He deals almost entirely with Western themes, then a few pages from the end, starts discussing Islam in a section called Islamic sociability and innovation. Not trying to make any points here, particularly regarding the topic of Heather’s post, except maybe that everything is more complicated than it looks; I just enjoyed this bit and have been waiting for an opportunity to share it. Apologies for the length. It goes on for several more pages.

The most challenging of all locks is perhaps the one that keeps Islam separate from unbelievers. And yet Arabic is the only language in which the word ‘man’ comes from the word ‘sympathy’: to be a man, etymologically, means to be polite or affable. In their proverbs, Arabs define themselves as ‘people who like to be liked’. Is it right to believe that there can be no end to the conflict of Muslims and their neighbours, since holy war (jihad) is an Islamic duty? The Islamic ideal of the good life is sociability, not war. There is almost no mention of war in the early, Mecca chapters of the Koran. The Prophet, on returning from one of his military campaigns, expressed pleasure that he could now turn from the lesser war to the greater war, which takes place inside each individual’s soul; and over the centuries the spiritual side of Islam has become increasingly dominant in the private lives of belivers. It is true that after Islam’s rapid military victories, the ‘sword’ verses of the Koran were held to have superceded the peaceful ones; but theologians, as usual, disagreed. Sayyid Ahmad Khan (1817-98), for example, argued that holy war was a duty for Muslims only if they were positively prevented from practicing their religion. It was the sense of not receiving due respect, and of being humiliated by colonialisation, that brought the ‘sword’ verses into prominence once more.

‘Beware of innovations,’ said the Prohpet. Superficially, it might seem that Islam is hostile to all modernation, but during its first 250 years it allowed great scope for individual reason. Jihad means not only war but effort. There was another kind of effort which was also encouraged – itjihad, which meant that the faithful were required to work out individually how they should behave in matters not directly covered my the holy texts. Those who studied the Koran and did their best to form their own opinions were assured of a reward from the Prophet, even if they were wrong. Divergences (ikhtilaf) were declared to be allowed by Allah by Abu Hanifah (700-67), one of Islam’s greatest jurists, founder of the school of law which has the largest following of all; and three other schools of law, though different, were considered to be all equally legitimate.

A time came when theologians demanded that the age of personal judgement (itjihad) should be closed, because their accumulated judgements had settled all possible uncertanties. But others insisted that it should remain open. Ibn Taymiyya (1263-1328), for example, though he inspired conservative forms of Islam, pointed out that a Muslim was obliged to obey only God and his Prophet, not ordinary mortals; each had a right to give his opinion ‘within the limits of his competence’. Both he and Abu Hanifah spent time in prison because other Muslims rejected their views. Schism and disputation have been a permanent part of Muslim history. Outsiders who have perceived it as a monolithic, unchanging totality miss completely the enormous richness of its traditions, the complex emotions that it shares with the history of other religions, and the significance of the Prophet’s statement that internal beliefs may be judged only by God. Though submission to God has been greatly emphasised by Muslims, the Qadariya sect insisted that humans had total freedom of will; the Kharajist sect even argued that it was legitamate to have a woman as a prayer leader (imam), and in one of its rebellions, led by Shabib b. Yazid, it used an army of women. The Azraqite sect made it a duty to rebel against an unjust government. The Shiites have alternated between quietism and challenge to the legitimacy of the secular state in their insatiable search for moral perfection.

That comment is good in showing the diversity of Islam. “Monolithic” is a word I have also used to criticize the way many people look at Islam and why I think everyone needs to know more. Currently though, there is a trend in thought in large parts of the Muslim world that a conservative Muslim is a better Muslim. I think this is partly a backlash against secularism, partly anti-Western sentiment, and partly encouraged by the spread of doctrines like Wahhabism by the recently wealthy Saudis via madrasses they sponsor throughout the Muslim world.

One of the most important things overlooked by apologists like Aslan when they make the claim that “it’s cultural, not religious”, is to recognize the brilliance of Mohammed by inextricably intertwining the religion with everyday life. This makes the idea of culture vs religion a distinction without a difference. And I think that is one of the reasons that many Muslims have such a difficult time being assimilated into the western societies that they emigrate to. If you look at all of the data from the Pew study, you find so many of the strict teachings of Islam are still very widely espoused, even among citizens in the western democracies, especially the slightly less egregious ones.

Good points. I think a lot of Muslims don’t really believe the extreme stuff, but they feel obliged to say they do in order to prove they’re Good Muslims. With so many doing that and scared to speak up, nothing changes. They see what happens to those who speak out, and it’s not pretty. It’s hard to speak out when you believe you are part of a tiny minority. That way the real minority retains power.

I think there’s an extra twist or two.

a) Many believe the extreme stuff.

b) Many don’t, but daren’t say so in the company of (a)

c) Both (a) and (b) daren’t say they do (or they don’t) in the company of non-Muslims, if there’s a chance it will get back to other Muslims.

Evidence: countless episodes of BBC The Big Questions when someone has tried to get and actual answer out of a Muslim: “Do you think apostates should be killed?” (a) want to say yes, but daren’t on British TV. (b) want to say no but daren’t in front of (a).

Much evasion ensues, “It’s not so simple. It’s very nuanced. There are contexts to consider.”

Until, if still pressed, if the questioner hasn’t given up, (a) or (b) take the easy route out: “Islamophobe! Why should I have to answer your questions? You presume to treat me like a criminal. …”

I think that’s true, and is a big problem. There’s pressure to be seen as a Good Muslim and any denial of widely accepted interpretations of the Qur’an especially, as you say, in front of non-Muslims, is seen as a betrayal of Islam. Showing solidarity in the face of a prejudice is important. Conservative Islam seems to be forcing itself on all Islam and moderate Muslims are portrayed as betraying Islam. The worst of the conservatives are forcing their opinions with physical force on other Muslims, frightening them into submission.

I am pleasantly surprised to learn that this is playing on CNN. Thank you for taking the time to compose articles like this Heather.

Reza Aslan has nothing to recommend him from my perspective. I think he is dishonestly self aggrandizing and intellectually dishonest. I don’t believe that he is completely unaware of how he misleads, misrepresents and bait & switches.

Meanwhile, it frustrates me that as evident all this is to me, and some others, that many people accept him just as he wishes to be taken, as a wise, fair, kindly scholar who should be listened to.

For example, take a look at the episode of The Daily Show With John Stewart, from the period during which John Oliver covered for Stewart long term, that featured Aslan as a guest. I genuinely like John Oliver. I think he is probably the best thing going on TV right now when it comes to getting to the root of important issues, and I agree with his opinion on such things most of the time. That’s why I was especially disappointed with that interview.

I would have just loved to have seen Christopher Hitchens and Reza Aslan on opposites sides of something like an Intelligence Squared debate.

Thanks, and I agree with all your comments about Aslan. I think his dissimulation is deliberate too, which is why I have such a problem with him. I haven’t seen him with John Oliver – I’ll look it up. I really like him as well so it’ll be a bit disappointing, but interesting nonetheless.

Aslan comes across as reasonable and is very well spoken. It’s quite possible Oliver didn’t know there was any controversy around him.

Aslan often does come across well. I tried to find the clip, but I couldn’t.

Hello Heather,

I don’t know if you will be able to view it in New Zealand, but try this link, Reza Aslan Extended Interview Pt.1. That is a Comedy Central link and is Part 1 of 3. If that doesn’t work let me know and I’ll try and find another.

I’ve never watched the extended interview, only the interview as it aired on the show. I’ll have to find the time to watch it.

Thanks so much! Yes, I could watch it. It was a good interview as far as it went, but as you said before, it seems Oliver might not know much about Aslan. It was also incredibly disingenuous of Aslan to leave the audience believing that he was a Christian! I bet he’s discovered that a book about Jesus by a Muslim in the US doesn’t sell as well. Perhaps the infamous Fox interview, in which my sympathies were all with Aslan, suppressed sales.

I must admit, it also left me wanting to buy the book.

Finally watched Zakaria’s programme. It is very interesting, particularly as it tells some truths not normally told on mainstream US tv. But his conclusions are confused and very frustrating because of what they leave out. I thought he was going to go there at the end when he started talking about broken politics and stagnant economics of many Muslim majority countries, but he backed off to it being all about a hatred of individual rights and the modern world in general. It’s all about them, nothing to do with us. Such a missed opportunity. And this despite quite openly alluding to US interventions that have killed a million or more Muslims and ruined countries, even stating that al-Awlaki never mentioned religion but only politics as the reason he turned against the US. His plea for tolerance is correct of course, but the problem won’t be solved by tolerance alone and while the elephant in the room is ignored.

I though Aslan was mostly ok in this too.

Great piece, Heather – thanks! I just wanted to share another take on Aslan’s response to Maher. It seems to me that the main issue lies in the last sentence: “By Bill Maher’s logic, those two groups are essentially the same because they share one fundamental belief.” This is a strawman – Maher isn’t saying that the Muslim word is essentially the same as ISIS, he’s saying that it has too much in common with ISIS.

If you take what Maher actually said and replace the relevant parts with the parts from Aslan’s response, you end up with a statement that seems pretty reasonable to me:

If vast numbers of Christians in the United States believe, and they do, that homosexuality is a sin, not only do Christians in the United States have something in common with the Westboro Baptist Church, they have too much in common with the Westboro Baptist Church.

(I’m not sure if “vast numbers” is fair, but according to http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/12/18/most-u-s-christian-groups-grow-more-accepting-of-homosexuality/ , 56% of “All Christians” say that homosexuality should be accepted by society, which suggests that 44% don’t think it should be accepted)

Thanks for your kind words. You’re right that if Aslan had said it the way Maher did, that would be much more acceptable.

There’s more to it imo – I think Aslan is glossing over this part a bit. DAESH thinks all homosexuals should be killed, and they do it. So do several Muslim-majority governments, and they do it too. That opinion is one that in many cases their populations share, as the stats show. While (too) many Christians think that homosexuality is a sin, the number who think they should be killed for it is tiny. So while 44% think that homosexuality is a sin, I’d be surprised if even 5% thought death was an appropriate punishment. That’s where the difference lies in many of the stats that Aslan can point to. There are a lot who share some of the ignorance of the WBC, but you won’t catch many Christian USians sharing the idea that atheists deserve the death penalty, while that’s government policy in Saudi Arabia as well as the caliphate.