It was my birthday on 10 December. I love the fact that my birthday is also International Human Rights Day. In New Zealand, it’s also the anniversary of the day smoking was banned in indoor public spaces, which makes bars, restaurants and workplaces much nicer places to be. 10 December is also the day the International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU) releases their Freedom of Thought report. (Full title – Freedom of Thought 2014: A Global Report on the Rights, Legal Status and Discrimination Against Humanists, Atheists and the Non-Religious.) It’s a good and comprehensive report, but its focus is such that New Zealand is classified in the “Severe Discrimination” category while the United States comes up smelling of roses. I find this bizarre.

It was my birthday on 10 December. I love the fact that my birthday is also International Human Rights Day. In New Zealand, it’s also the anniversary of the day smoking was banned in indoor public spaces, which makes bars, restaurants and workplaces much nicer places to be. 10 December is also the day the International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU) releases their Freedom of Thought report. (Full title – Freedom of Thought 2014: A Global Report on the Rights, Legal Status and Discrimination Against Humanists, Atheists and the Non-Religious.) It’s a good and comprehensive report, but its focus is such that New Zealand is classified in the “Severe Discrimination” category while the United States comes up smelling of roses. I find this bizarre.

(Indi at Canadian Atheist has written a good summary of the report as it relates to Canada.)

Within minutes of reading the IHEU report, I came across yet another anti-atheist piece in the American media by an ignoramus called David Marcus entitled Seven Things Atheists Get Wrong. With the backdrop of a huge picture of a grinning Pope Francis, Marcus makes an ill-informed assault on atheists.

The first thing he wishes atheists knew is, “Religion Is About Morality, Not Creation Myths”. He attacks what he sees as atheists’ obsession with children being taught creationism and intelligent design over Evolutionary Theory. To Marcus, that isn’t important because religion is all about morality. Marcus is clearly of the opinion that morality is the preserve of the religious, and atheism is by definition immoral.

Atheists Are Moral People. Not only are we moral people, our morals are, on average, better than theists. After summarizing twelve studies on the morals of atheists Zuckerman wrote in his 2009 report ‘Atheism, Secularity, and Well-Being: How the Findings of Social Science Counter Negative Stereotypes and Assumptions‘:

It is often assumed that someone who doesn’t believe in God doesn’t believe in anything, or that a person who has no religion must have no values. These assumptions are simply untrue. People can reject religion and still maintain strong beliefs. Being godless does not mean being without values. Numerous studies reveal that atheists and secular people most certainly maintain strong values, beliefs, and opinions. But more significantly, when we actually compare the values and beliefs of atheists and secular people to those of religious people, the former are markedly less nationalistic, less prejudiced, less anti-Semitic, less racist, less dogmatic, less ethnocentric, less close-minded, and less authoritarian.

Teaching children accurate science is important too. Creationism and Intelligent Design are not science and their theories are simply wrong. Anyone who says otherwise is mistaken or lying. They have no place in any reputable educational institution, and to teach them to children as anything other than a religious myth is dishonest.

Marcus also mocks some of the aids we atheists use on the internet to mock creationists like the “… jokes about cave men riding dinosaurs … ‘, but you have to admit, some of them are very funny:

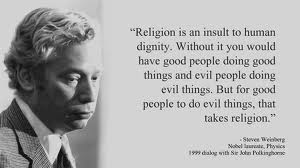

The next thing Marcus wishes atheists knew is, “Religion is the Foundation of all Morality, Not Merely an Expression of it”. He goes on to say:

All of us, whether atheist, agnostic, or a member of a religion, practice morality based on religion. Without religion there would never have been morality. There was no peaceful, Adamite paradise of moral choice which religion sullied millennia ago. Before religion, there was murder and rape and all manner of horrors just as there are today. It was religion that first sought to constrain human actions through a moral code, not science.

I don’t even know where to start with this statement, it’s so stupid. He really seems to believe that before religion came along there was anarchy – that people hadn’t worked out theft was wrong before Moses came down from communing with God in the mountains.

This attitude is one that scares atheists – the idea that a god and religion are required for people to be moral. It means that the only reason religions people are moral is the promise of heaven or the fear of hell. That means they’re not moral people at all, they’re selfish and fearful people. Atheists are good without god. We take responsibility for our own behaviour, we don’t blame evil spirits when we get it wrong, and we don’t consider anonymously confessing to a supernatural being sufficient for forgiveness.

This attitude is one that scares atheists – the idea that a god and religion are required for people to be moral. It means that the only reason religions people are moral is the promise of heaven or the fear of hell. That means they’re not moral people at all, they’re selfish and fearful people. Atheists are good without god. We take responsibility for our own behaviour, we don’t blame evil spirits when we get it wrong, and we don’t consider anonymously confessing to a supernatural being sufficient for forgiveness.

The third of Marcus’s wishes is that atheists knew, “Religion was the Foundation of Society, Not an Addition to it”. He refers to what he calls Marcel Gauchet’s “insightful” essay that argued “without religion there would be no state”.

I’m not a philosopher, a sociologist, or an anthropologist, and perhaps one can weigh in here, but to me this doesn’t make sense. The development of a state is surely a normal stage in our evolution and could easily happen without religion. It would need codified laws of behaviour, but religion is not required to develop these.

Marcus’s next anti-atheist attack has me a bit mystified. I’m not entirely sure what he’s talking about here:

4. Atheists Do Believe

The question most often posed to atheists who complain about the presence of the Ten Commandments or a creche in public spaces is, “Since you don’t believe, why does it bother you so much?” This is the wrong question. The right question is, “Since you do believe, why does it bother you so much?” Because most atheists do believe, and I stress the word believe, that they are capable of understanding right from wrong. They provide no scientific justification for such a belief because no such scientific justification exists.

I just don’t know what’s he’s talking about. What is our belief? Atheism is simply the lack of belief in any god or gods, so he can’t be talking about that. And the Ten Commandments. What’s that about? In the United States, the First Amendment means that the Ten Commandments shouldn’t be displayed in a public space. Because of the dominance of Christianity they have been displayed in many places, but that doesn’t change the fact that it’s illegal. To attack those who point it out is irrational. Some Christians do seem to think there’s a War on Christianity, but that too is irrational.

I just don’t know what’s he’s talking about. What is our belief? Atheism is simply the lack of belief in any god or gods, so he can’t be talking about that. And the Ten Commandments. What’s that about? In the United States, the First Amendment means that the Ten Commandments shouldn’t be displayed in a public space. Because of the dominance of Christianity they have been displayed in many places, but that doesn’t change the fact that it’s illegal. To attack those who point it out is irrational. Some Christians do seem to think there’s a War on Christianity, but that too is irrational.

Number five on Marcus’s list of things he thinks atheists should know is “Science Can’t Teach Us Right From Wrong”.

Well, I hate to disappoint you Mr Marcus, but atheists already know that, and you’d be hard-pressed to find an atheist who claims such a thing. What science can teach is what is real and what is not, what is true and what is not. I recommend Richard Dawkins book ‘The Magic of Reality: How We Know What’s Really True’ to you.

Well, I hate to disappoint you Mr Marcus, but atheists already know that, and you’d be hard-pressed to find an atheist who claims such a thing. What science can teach is what is real and what is not, what is true and what is not. I recommend Richard Dawkins book ‘The Magic of Reality: How We Know What’s Really True’ to you.

Number six is “Religion Complements Science, It Doesn’t Oppose it”. He makes the statement:

This is where religion, far from being the natural enemy of science, comes to its aid. Just as believers must always fight nagging doubts about the truth of their beliefs, the atheist must fight nagging beliefs when confronted with moral choices. Just as there is no paradox in a believer knowing that science can reveal important details of how the physical world operates, there is no paradox in an atheist knowing that religion and its ancient history of moral investigation is relevant to moral understanding.

If science complements religion, why has religion spent so much of its history suppressing it? The answer is obvious of course: science often proves claims made by religion are wrong and rather than admit they were wrong, they attack science. It took the Roman Catholic Church hundreds of years to “forgive” Galileo for speaking the truth. At least Galileo was allowed to live – others were burnt to death for the same “crime”. There are countless examples of science and scientists being attacked for exposing lies in religion. In the United States literally billions of dollars are spent in an attempt to force the lies of Creationism and Intelligent Design on children.

And as for moral choices, we really don’t need religion to help us make them. In fact, as Zuckerman’s study referenced above shows us, atheists do a helluva a lot better when it comes to making moral choices than your average theist. From Zuckerman’s study:

I would argue that a strong case could be made that atheists and secular people actually possess a stronger and more ethical sense of social justice that their religions peers. After all, when it comes to such issues as the governmental use of torture or the death penalty, we see that atheists and secular people are far more merciful and humane. When it comes to protecting the environment, women’s rights, and gay rights, the non-religious again distinguish themselves as being the most supportive. And, as stated earlier, atheists and secular people are also the least likely to harbour ethnocentric, racist, or nationalistic attitudes. Strange then, that so many people assume that atheists and non-religions people lack strong values and ethical beliefs – a truly groundless and unsupportable assumption.

Marcus finishes with, “Ignorance of Religion is Ignorance of History, For Atheists and Everyone”.

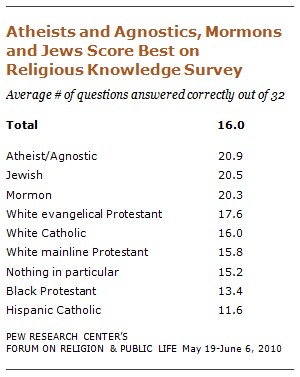

Again, I think you’d struggle to find an atheist who disagrees with that. And unlike your average theist, we atheists walk the talk. A Pew Research Center poll from 2010 shows that atheists and agnostics have a better knowledge of religion than any religious group. If you go to the website you can actually answer a selection of the questions used in the survey. I got them all correct, and I suspect any of the so-called New Atheists that the media so loves to hate, would too.

Again, I think you’d struggle to find an atheist who disagrees with that. And unlike your average theist, we atheists walk the talk. A Pew Research Center poll from 2010 shows that atheists and agnostics have a better knowledge of religion than any religious group. If you go to the website you can actually answer a selection of the questions used in the survey. I got them all correct, and I suspect any of the so-called New Atheists that the media so loves to hate, would too.

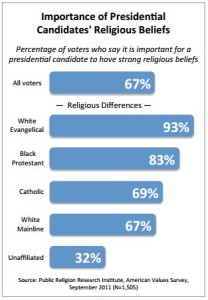

This constant bigotry against atheists in America is frankly appalling. In my piece, “America Hates its Best Citizens: the Atheists,” I presented the Pew Research Center statistic that demonstrates atheists are among the most hated Americans. There are further statistics that show America’s anti-atheist bias. For example, in 2011 the Public Religion Research Institute conducted a survey that questioned people about US presidential beliefs. The results showed that two-thirds of Americans would be somewhat of very uncomfortable with an atheist president. When the results are broken down by political affiliation, we see fully 80% of Republicans and 70% of Democrats were opposed to an atheist president. (56% of independents were somewhat or very uncomfortable with an atheist.)

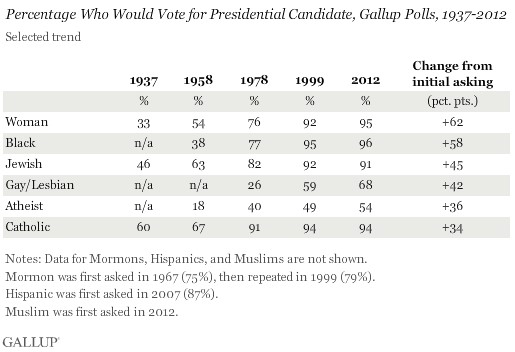

Gallup showed similar results in 2012, where a survey showed only 54% of Americans would be willing to vote for an atheist candidate as president. Gallup has been asking this question since 1958, and although perception of atheists has improved in that time, it’s still poor.

The Public Religion Research Institute’s survey further showed that two-thirds of Americans considered it important that a president had ‘strong’ religious beliefs. This figure rises to 93% for white evangelicals, 83% for black Protestants and 69% for Catholics.

The Public Religion Research Institute’s survey further showed that two-thirds of Americans considered it important that a president had ‘strong’ religious beliefs. This figure rises to 93% for white evangelicals, 83% for black Protestants and 69% for Catholics.

The Public Religion Research Institute although faithfully reporting the statistics, favours religion, and was thus determined to show atheists in the worst light possible. On pages eleven-twelve of the 2012 report they presented anecdotes of from those who had left religion. They included, “One respondent cites his military experiences as the reason he left the Catholic Church: “I was raised in a Catholic house, and one commandment is thou shall not kill. In the army, I was a sniper, so for me to do my job, it was something I left behind.” The conclusion we are obviously supposed to draw here is that not believing in God makes you a killer.

The animus against atheists around the world is sickening. There are still countries that have the death penalty for atheists, and it is used. Despite that, the number of atheists continues to grow, and by the end of the century it’s likely we will be in the majority worldwide. But don’t worry theists; we are good people and we won’t treat you the way you treat us. We believe in the freedom to believe, as well as the freedom not to believe.

Regarding atheists and faith I recently read something Penn Gillette said which I like: You’re right. Without religion people will murder, rape, and pillage as much as they want. I do it now! i murder as much as I want. I rape as much as I want. I pillage as much as I want. I don’t want to doany of it.” (paraphrasing.) But my response to people like Marcus is always mixed with a little confusion. Really? With a church to go to you would feel free to rape my wife? Murder me for my lawn mower? It truly makes no sense to me.

Yes – I love that quote from Penn Jillette – I wish I’d remembered about it when writing the article.

From my personal experience, the table that shows the scores for groups with the most religious knowledge, is pretty accurate. My experience with my white Catholic side of the family will make you nuts. They didn’t even know Jesus was a Jew!!

There must be a lot of eye-rolling moments at your family gatherings 🙂

Usually the eye rolling is me over the Internet or me finally not being able to take it anymore & saying something on the FB pages.

“Science Can’t Teach Us Right From Wrong”

But by teaching us what causes us to have feelings and opinions about what’s right and wrong it can show that if science can’t tell us the difference in some specific case then nothing can, and right and wrong are only basically opinions, preferences.

There is no evidence of any objective nature of morality that is not wholly determined by our evolved and socially and linguistically constructed morality.

Science can often give us the additional insight from which to make better informed moral decisions.

Where we don’t explicitly use ‘science’ to inform moral decisions that’s because the decision is trivial, or has an empirically well established outcome – though many old traditional moral prescriptions and proscriptions can be changed in the light of a few short centuries of scientific enquiry.

The very notions of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ are open to scientific investigation, by cognitive, psychological, sociological studies. It’s in that light that we now reject many old theologically determined ‘rights’ and ‘wrongs’, and why some that are claimed to be theological in origin have a better natural anthropological explanation.

In this wider context it’s just as fair to say “Science can tell us right from wrong”.

I’d be interested to see examples of:

1 – where science can’t provide useful additional information in determining right from wrong;

2 – where some other imagined ‘way of knowing’ could provide any better determination of right from wrong.

Ron, I feel that science in the form of chemistry, physics and biology etc may go some way towards the determination of what is right or wrong but I believe that other disciplines such as philosophy, anthropology and sociology are better tools. In philosophy, for instance, you look at concepts such as the the maximum benefit to the greatest number of people, how people offend against their own better nature and a host of other concepts. History and sociology are also useful disciplines in determining and evaluating ethical concepts.

However, I see records of religion such as the Bible, Q’uran,the Tora and saying of Confucious as interesting histories of ethical concepts and also partly a determinant of ethical values – providing of course that people practise them. Religion is therefore important from a historical, anthropological and sociological point of view regardless of any belief or otherwise that people may hold.

An understanding of what a particular society sees as “wrong” or “right” tend to change over time and will no doubt continue to do so. If science is used as a tool to determine what is right and wrong we run the risk of putting science up as the new religion. My argument is that it is more valid to investigate, analyse and describe ethical principles rather than determine them by religion, science or anything else for that matter.

Rob, I think you are reaching with some of your own priuspposetions and ideologies a little bit with some of your responses. The only leg religion now stands on is linked to morality? Really? I think that is true if you only understand religion from the definitions of the anti-religious and if you are only listening to the arguments made by the religious defending themselves against atheists that are telling them their religion is worthless. I think it’s a quite shallow understanding of religion to look at the Dalai Lama and say that the only leg he has to stand on is that he is has some link to morality and others do not.You are making it seem that I’m saying you can still be good with God as if it’s a stretch of the imagination to imagine that there could be good people that believe in God. When all i’m doing is pointing out that you can be good with or without a belief in God. To take a side’ on that issue is to wrongly understand religion, humanity and the direction of society. I’m not suggesting the same old argument to ignore the thousands of dead and the horrors of the world, I’m simply refusing to attribute evil done evil by religious people to religion as if religion in and of itself has the power to corrupt humans. Humans (from my belief) are already corrupt, or have the potential to be corrupt, so to then point to external factors such as religion and blame their evil on that instead of humanity itself taking responsibility. Which if you can at least believe that (that humans have the capacity of both good and evil) then religion can be viewed a lot differently as not the cause of good and evil but rather the attempt to acknowledge and define it.If you think the core components of Christianity are immoral I would love to know what you think those components are? I think I have a pretty strong moral compass and I also hold to the Christian faith so I don’t follow?I think though that JMW is onto something in needing to define someone as religious and someone as not religious. For instance, when you say ENTIRELY religious what does that mean exactly? I would consider myself very religious (probably entirely if we were really to lay it out). What makes that community entirely religious and say an atheist anarchist activist’ who uses violence to destroy corporations and save the environment not religious? Is it because one uses the term God to describe their beliefs and the other refuses to use the term? Is the only way to distinguish between someone entirely religious and someone who is not religious (which I assume is probably your view of yourself?) that one claims that God is their muse and the other claims science is?

Martin,

I think philosophy has a long history of formalising moral dilemmas but goes not way to actually answering them. It can use its methods of reasoned argument to illustrate deductively how various conclusions can be drawn from various premises, but gives no evidence to support the premises; or where it does rely on observed premises it is using empiricism, the tool of science.

I think what you say is covered by the thorny issue (a thorn in the side of philosophers at least) of the definition of science. Traditionally it is held to be what we have come to know as the hard sciences; and even scientists in the hard scones have rejected some of the soft sciences as being science. But what we have come to learn through various sciences is that humans are empirical beings. The neutrons of the brain are not significantly different from the neutrons of the peripheral senses. Essentially, the activity of the neutrons of the brain is to interact with each other – they are localised empirical cells, interacting through chemistry – where even the action potentials are based on chemical (ion) transfers rather than electron flow; but then of course chemistry is based on electromagnetic interactions. In all there is nothing about humans, or any mammals, or any precursors, even back to simple cells, that is not engaged in physical interaction. Lacking anything that resembles the philosophical notion of ‘mind’, such that the ‘mind’ is an old but persisting model of the brain’s activity, our only reasonable inference is that all human knowledge acquisition is empirical in one way or another, and that even reason itself is some complex physical interaction in the brain.

As such, the demarcation of various sciences and philosophy, are somewhat arbitrary. The sciences use many of the tools of philosophy. Science grew out of natural philosophy. And anthropology and sociology are certainly sciences.

“In philosophy, for instance, you look at concepts such as the the maximum benefit to the greatest number of people”

And how do you measure benefit, once defined? Science. The problem is that in the history of philosophy it has never really got to grips with this because it has relied too little on empirical data in a modern scientific sense, but rather on the opinions of philosophers that are conjured up from the biases of their own personal and cultural origins – so you get vastly different schools of philosophy.

“how people offend against their own better nature and a host of other concepts.”

Another problem of philosophy is that it is full of these ill-defined notions, like ‘better nature’.

Sociology is a science – it just happens to be an extremely difficult science, since it is trying to determine trends and laws from such complex entities as groups of humans. A significant problem for these ‘soft’ sciences is that they are difficult in this sense, but that this in itself makes them susceptible to being taken up by cranks and open to pseudo-science.

History is another example of an empirical ‘science’, though historically, ironically, history itself is late to the use of science. Part of its problem is that it has to rely a lot on recorded history, recorded at times when the methods of science where rather sparse to say the least. Hearsay is what a lot of it amounts to, unfortunately. A case in point is the way in which Christian theist scholars rely on a source like Josephus, when in fact Josephus has only a few references to Jesus, and they are only reports (hearsay) of what he heard about or from Christians. Artefacts are the real evidence of history, but they have to be interpreted. History should apply the methods of science, but it still remains a very difficult science.

But, where all these ‘sciences’ contribute usefully to morality they do so by informing us about what we are and where we came from. And it is in the context of that empirical data that we decide what we want to do about it regarding morality.

I would say that religious texts are, for want of a better expression, echoes of natural human feelings and culturally developed thoughts about morality. But because of the way religions embody so many other aspects of human behaviour, political control, behavioural control, they reflect so many errors about morality. Though some religious moral matters are more about observances – e.g. not eating pork – that might in some cases have come out of some genuine need in the past, they evolve into rather unnecessary moral codes that are not based on any current empirical bases. What is wrong with eating pork? On other issues, what is wrong with Victorian women showing their ankles, being alone with gentlemen without a chaperone, …

Even today you’ll find people that deem tattoos to be morally repugnant themselves, or an indicator of bad moral character – when rather simple sociological studies would show that many people with tattoos today are decent but expressive people. Of course there are issues like this that seem ‘obvious’, but the problem is that what appears obvious is not always the case, and so if we want better answers than personal biased opinion can provide we do need science.

Religion is important historically, because it explains much about what religious believers believe today. As such the study of religion itself benefits from more rigorous unbiased study than many theological departments like. More ‘scientific’ approach would be better than the ‘unscientific’ nonsense that we get from religious scholars that decide that absence of evidence against is evidence for acceptance. How often do we see them claim there is no reason to disbelieve the gospel stories because we cannot show them to be fraudulent or unreliable. Studying religion ‘scientifically’ is quite different from practicing religion, no matter how well steeped in one’s religion a theist is.

“An understanding of what a particular society sees as “wrong” or “right” tend to change over time and will no doubt continue to do so.”

And I think one of the greatest contributing factors to a more liberal morality today is the scepticism and demand for evidence that has become common throughout society thanks to the success of science. We all tend to apply more ‘scientific’ assessments of claims and evidence than we did in past times when the local witch tossing a few marked bones on the ground. Astrology is read far greater scepticism than it once was. There’s along way to go, and much superstition to overcome, but we are improving.

“If science is used as a tool to determine what is right and wrong we run the risk of putting science up as the new religion.”

I’m not saying that couldn’t happen, but it’s highly unlikely, since from early scientific modernism, through post-modernism, and post-post-modernism, the methods of science have been exposing their won failings – it is an inherently self-improving set of methods. We go through phases where a science is taken to be more reliable than it actually is, but it’s always some additional epirical observations that show where it has failed. The alternatives are nothing more than scaremongering and denials. It might be the case that some GM foods turn out to be dangerous – but it’s empirical observation that will make that first apparent, and it will be science that determines it and distinguishes fact from counter-hype.

“My argument is that it is more valid to investigate, analyse and describe ethical principles rather than determine them by religion, science or anything else for that matter.”

My argument is that to investigate, analyse and describe is the basis of science. So I have to ask where the principles that are to be investigated come from? We can start out with the principles from religion, but as I explained above, such principles can be examined scientifically: what is it about eating pork that makes it worthy of its avoidance being made a moral code? The morality of abortion relies on claims about suffering – to what extent does science show that a zygote with no neutrons suffers? When abortion is addressed from a theological basis, that the ‘soul’ enters at conception, what evidence is there to support such a notion? Science of biology tells us a lot about the similarities and differences between humans and other animals, to the extent that chimps and other primates seem to have something like human suffering, and self-awareness something like a child, and that has been evidence that is now being used to influence debate about the rights of such animals, and even their personhood.

I think the point that science is unlikely by its very nature to become a religion is an important one. Scientists are constantly questioning and checking. If evidence shows that what was previously thought to be incorrect isn’t, scientists abandon it. Further, those scientists that cling to disproven hypotheses are sidelined. Theories are only accepted until a better one comes along. With faith, the opposite is true. Those who cling to their faith in the face of overwhelming evidence that they are wrong are admired.

BTW Ron, if possible, please try to keep the comments shorter than my article. 🙂

HAHA@keep comments shorter than the article! Don’t worry Ron, I also got “told off” before so you’re in good company.

As for science, you guys might want to refer to Peter Woit’s blog “Not Even Wrong”

http://www.math.columbia.edu/~woit/wordpress/

It is pretty heavy reading, especially if you do not come from a scientific background, but it basically shows how science used to be considered something where you could take measurements and when you got the wrong results, you could say the theory was wrong.

However, some of the leading theories on the origin of the universe are now such that they can never be “proven” wrong – so even if you do not get experimental results to support your theory, you can simply change the parameters and then try again! This is why the blog is titled “Not Even Wrong”, and Peter Woit argues that a lot of these theories are driven by trying to obtain extra funding or because someone has worked on them their entire life and doesn’t want to give up on them.

Hi Heather, great article! I was wondering if some of the distrust of atheists may be due to the lower nationalism of many atheists. My own lack of nationalism is partly because I think there are lots of great ideas out there, and one country doesn’t own them all. I’ve also met a lot of great people from around the world. Back to the point, I think sometimes people mistake open-mindedness for indecisiveness, or lack of loyalty.

Hi Todd. Thanks 🙂 . I think you might be right about America. The idea of American exceptionalism seems to be a strong one. Anyone that admits another country might have a better idea about something is often seen as unpatriotic and a betrayer. There are other countries that do that too – Russia, China and Japan come to mind – but America hasn’t suffered in the same way as they have because America’s fault in this area is ameliorated by immigration. Other countries see improving their country as a patriotic act, and are happy to take good ideas wherever they come from.

“smoking was banned in indoor public spaces, which makes bars, restaurants and workplaces much nicer places”

Not for smokers it doesn’t.

That pie chart with the Christian slice complaining about being oppressed is silly. Based on the same logic you could have mocked South African blacks for complaining of oppression during apartheid since they were in the majority. Obviously the situations are not comparable, but the pie chart is implying the merely being the majority makes it impossible to be oppressed.

Or Russian serfs, or peasantry almost everywhere through almost all of history…

Now, if it were of the identifications of senators or suchlike, that would make more sense. I assume it isn’t but it has no title.

Your analogy is invalid as blacks in apartheid-era South Africa, or Russian serfs had no political power. In the US, all American presidents and almost all political representatives, ever, have been Christian. Currently, well over 90% of members of Congress are Christian. Only one is openly atheist. It many parts of the country, it is impossible for someone openly atheist to be elected to political office. The same cannot be said about Christians.

And anyway, where’s your sense of humour? It’s an ability to laugh at themselves that creates people who think terrorism is an appropriate response to satire.

The graphic doesn’t say: “Christians: It is silly to think of yourselves as oppressed since you are a majority, and the majority of people holding political power now and in the past have been Christian.” It says: “Christians: you are the majority! Therefore it is silly to think of yourself as oppressed.”

Where is your logic? It’s an inability to think logically that creates people who think terrorism is an appropriate response to satire.

Where is your sense of humour? It is a cartoon. I didn’t make it up, but I do think it makes a point in the way that satire so often does.

It’s not an inability to think logically that creates people who think murder is an appropriate response to satire. If that was the case the human race would be wiped off the earth in no time flat – belief in the supernatural is not logical; that’s why it requires faith.

Let us consider a joke from Family Guy in which a Muslim terrorist goes to heaven only to find that the promised 72 virgins are male geeks. Funny? My Collins dictionary from ’77 (first printed in ’56) defines a virgin as, “a girl or woman who has not had sexual intercourse with a man; a maiden.” The sense of the term extended to include males is recent, and I would not be surprised if modern societies are the only such to ever have had a term for a person, male or female, who has not had sexual intercourse. I don’t know Arabic but I would be willing to bet that the term in the Koran cannot refer to a male. ‘Maiden’, though once synonymous with ‘virgin’, would then be a better translation into English of the term in the Koran. So the joke only works because of the translation of an Arabic word to an English word which has recently acquired a historically unprecedented extension of its meaning beyond the meaning of the Arabic word, and wouldn’t have worked if it had been translated into an until-very-recently synonymous term. These considerations occurred to me almost instantaneously upon encountering the Family Guy joke. To me this makes the joke stupid rather than funny. To others I am just being humourless and pedantic. Likewise as soon as I saw that pie chart I thought, “majorities are easily and often oppressed”, now if this had occurred to me a little later maybe I would have already been amused by the joke “Ha Ha! complaining of oppression while being an overwheling majority. Silly Christians!” It’s not my fault I’m not more slow-witted. More seriously, I suspect it is about context. If your thoughts are limited to the context of English terms you would find the Family Guy joke funny. If your thoughts were limited to the context of Western democracy and of power residing in politicians maybe the pie chart would be funny.

As for an inability to think logically creating murderous extremists: I was not being entirely serious (where is your sense of humour?). I was just reacting to your having drawn a parallel between me and the murderers of cartoonists because I said I did not find a single cartoon funny.

I thought the Family Guy joke was funny, although I too was aware of the history and etymology of the word “virgin”, and recalled it at the time. You are correct that majorities are often and easily oppressed, but there’s a time for literalism and a time for keeping it in the back of your mind.

The Greek work that has been translated into Latin and English as “virgin” for Virgin Mary, doesn’t actually mean virgin either. I’m sure the Catholic Church has been aware of this for centuries, but it suits them to ignore it.

There’s an alternative translation for the Arabic word usually translated in the context you refer to above as virgins. It is white raisins. When you read the whole theory in context, the raisin translation makes more sense. However,”virgins” are more popular among the type of men who, in my opinion, are likely to be able to be persuaded to be suicide bombers.

It’s not so long ago that “gay” didn’t also mean homosexual, but that doesn’t make using it in that context wrong nowadays.

My point is language is constantly evolving. I’m sorry if you feel I’ve been too hard on you, but given that I consider this site an extension of my own home (read the rules), I felt you were being a bit petty.

I wasn’t objecting to the evolution of language or calling new usages incorrect. The joke is premised upon ‘virgin‘ also being able to refer to a male, so maybe when the Muslims are promised 72 ‘virgins‘ males could be meant. But they aren‘t promised 72 ‘virgins‘ they are promised something in Arabic. Something which either means ‘maidens‘ or, as you say, white grapes (o_O). I guess we’ll just have to disagree as to whether this ruins the joke or not.

I did, in a way, feel you were being a little hard on me, but I found this slightly amusing rather than disagreeable.

To make up for coming into your home and coming across as petty, I hope you‘ll accept the following alternative response, in place of the customary bottle of wine (even if this particular bottle is a cheap one):

Ha! The satire, eh!

Heather Hastie.

I hate haters, eh!

Hear atheist, eh!

The ‘eh‘s are a tribute to your kiwiness, and totally not just because that’s all I could make work.

Very good! That gets you forgiven – you can come back. 🙂