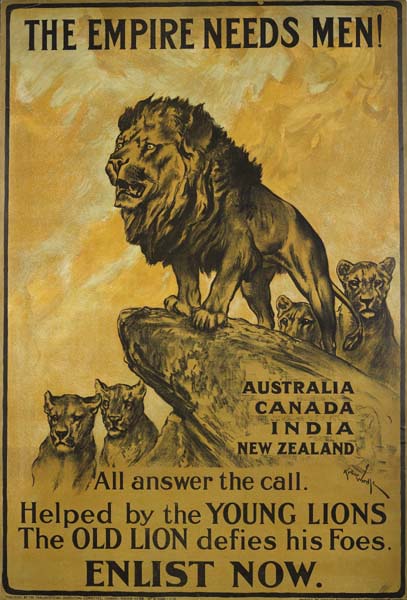

It’s 100 years since the start of the First World War. From New Zealand’s point of view, the Great War started at 2300 GMT on 4 August 2014 when Great Britain declared war on Germany. As part of the British Empire, that meant we were at war too. My grandfather volunteered and trained in rural Otago before being shipped to Egypt to fight. Later he was transferred to the Western Front and fought from the trenches. By 1917 he had been promoted to Sergeant, and was part of a sortie into no-man’s land. He and the others on the mission were trapped for eight hours when they were on their way back; they had been heard by the Germans. Eventually, with dawn not far off, they decided to make a run for it. They all made it back alive, although as the last one to dive back over the parapet, my grandfather had his buttocks shot off – an injury bad enough to see him sent back to England to recover.

It’s 100 years since the start of the First World War. From New Zealand’s point of view, the Great War started at 2300 GMT on 4 August 2014 when Great Britain declared war on Germany. As part of the British Empire, that meant we were at war too. My grandfather volunteered and trained in rural Otago before being shipped to Egypt to fight. Later he was transferred to the Western Front and fought from the trenches. By 1917 he had been promoted to Sergeant, and was part of a sortie into no-man’s land. He and the others on the mission were trapped for eight hours when they were on their way back; they had been heard by the Germans. Eventually, with dawn not far off, they decided to make a run for it. They all made it back alive, although as the last one to dive back over the parapet, my grandfather had his buttocks shot off – an injury bad enough to see him sent back to England to recover.

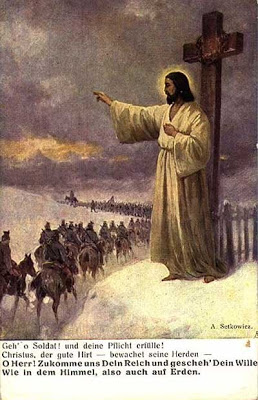

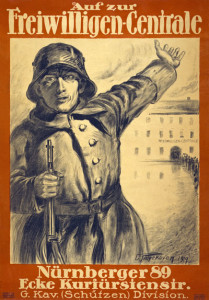

In a letter my grandfather sent home he wrote of how proud he was to be chosen for the mission. This lead me eventually to wonder about what role religions had to play in a generic sense. Most people, whether military or civilian, need reasons to fight a war. In the Great War, governments provided those reasons, but in every European country the churches became their government’s mouthpieces. They persuaded their worshippers God was on their side and that the enemy was evil in a religious sense. Christ Church canon Henry Scott Holland said,

We British pray that God will help Britain, not because she is Britain, but because she is righteous … (Hoover, p. 6)

The Lord Bishop of London, while assuring his flock, “this is a Holy War” said,

We are on the side of Christianity against the anti-Christ. (Hoover, p. 24)

In Germany, most sermons were directed against Britain as its people were told by their rulers that it was Britain who masterminded the attack against them – it was the public’s belief that they were the victims, not the aggressors. (Hoover, pp. 51-2, 67, 76) Pastors preached everywhere that Germany was the victim of Britain’s lies and jealousy, but that God was on the side of truth. (Hoover pp. 51-6) In general, the churches of all the belligerents took a strongly nationalistic and patriotic perspective, supported their governments during the Great War, and exhorted their congregations to do the same.

Although they completely reversed tack on its outbreak, most British churches had been involved in promoting peace movements in the years leading up to war. There had been Christian peace movements in Britain since the early nineteenth century, dominated by the Quakers, but which had members of all denominations. By the early twentieth century, their memberships were growing, largely in response to German militarism. (Moses, p. 26) The Church of England considered itself ‘… the nation’s independent moral conscience.’ (Moses, p. 27) In 1911 they established their own Peace League ‘… in the belief that war was the result of people’s failure to appropriate the Gospel, and that therefore, the Church’s task was to make the Gospel heard in the corridors of power as well as in the parishes.’ (Moses, p. 26)

By the churches, there is a lot made of the fact that before the war, there seemed to be a new sense of coming together between the two great Protestant empires of Britain and Germany. Joint conferences, attended by senior members of both national churches (but organized and led by Quaker J Allen Baker) were held in each country in 1908 and 1909. Attendees were encouraged by them, but in reality, both the Protestant and Catholic clergy in Germany mostly ‘opposed or ignored’ the peace movement. (Moses, p. 23) There were some fundamental differences between English and German Protestantism that made any coming together illusory.

There was never a remote chance that the British and German churches could have combined forces to advance the cause of peace before their respective governments. (Moses, p. 24)

Luther’s doctrine of Zwei-Reich-Lehre (Doctrine of the Two Kingdoms) had been the basis of the thinking of all leading German philosophers and theologians since his time, so that by the early twentieth century the Lutheran-Hegelian tradition was imbued in German Kultur. (Moses, pages 24-6) Luther’s Protestantism, while giving individuals a strong and prescriptive moral code, gave the state free rein in all its actions. Luther had basically swapped the state and the Pope as the figure of authority – it was now state leaders who were infallible and whose actions were beyond question. Protestantism in Britain took many forms, but it was dominated by the Church of England which owed its origins to a more humanist Erastian tradition. To convince a German that the state should be answerable to the same rules as its people would have been like trying to convince a Brit of the opposite.

Luther’s doctrine of Zwei-Reich-Lehre (Doctrine of the Two Kingdoms) had been the basis of the thinking of all leading German philosophers and theologians since his time, so that by the early twentieth century the Lutheran-Hegelian tradition was imbued in German Kultur. (Moses, pages 24-6) Luther’s Protestantism, while giving individuals a strong and prescriptive moral code, gave the state free rein in all its actions. Luther had basically swapped the state and the Pope as the figure of authority – it was now state leaders who were infallible and whose actions were beyond question. Protestantism in Britain took many forms, but it was dominated by the Church of England which owed its origins to a more humanist Erastian tradition. To convince a German that the state should be answerable to the same rules as its people would have been like trying to convince a Brit of the opposite.

Almost everywhere in Europe the immediate … consequence of war was an outbreak of apparent social … unity.’(Strachan, p. 165)

Most religious organizations that had followers on both sides took a neutral stance, but those same followers took a strongly nationalistic and patriotic stance in their own countries. Throughout Europe, a conservative, religious, landowning aristocracy which was tied closely to the military was still an important political force. (Strachan, p. 170) Before the war, they had been in decline as liberal and socialist influences became more prevalent, but as soon as war broke out, each country’s religious groups found a new relevance. Even in Republican France, the Catholic clergy reported that as the country mobilised, people ‘both in and out of uniform’, were flocking back to the churches. (Smith et al, p. 28)

Pope Benedict XV was determinedly neutral but the Catholic Church in France strongly supported the war. (Stevenson, p 265) This, in conjunction with the fact that France had been attacked by a country that had already occupied part of it for more than 40 years (German-occupied Alsace-Lorraine), meant there was strong grass-roots support for the war. The Church, for its part, pointed out that the war met its definition of a Just War and 25,000 clerics mobilized, the majority of whom fought and died alongside their countrymen rather than serving as chaplains. In August 1915, the following was published in La Revue du Clergé Français:

France cannot lose. The world would be denied that of which she is the exquisite adornment, the Church that of which she is the tireless apostle, and God himself the service of a generous knight. (Smith et al, p. 28)

Alsace-Lorraine (in pink), which had been occupied by Germany since the Franco-Prussian war in 1870.

Until recently, the largely Catholic army officers and the Republican government had been at odds. The coalition government of 1899 had been determined to break the power of the Catholic Church and the professional officer corps. (Smith et al, p. 17) Episodes such as the Dreyfus Affair, which began in 1894 (the legacy of which lasted well into the 20th century) was one of the prompts to finally passing on 9 December 1905 a law separating the churches and the state in France. On the outbreak of war though, the nation pulled together. In the villages, it was still the church bells that rang to declare war. Despite the fact that the 1905 law guaranteed freedom of worship, Protestants and Jews were often excluded from the mainstream by the Catholic majority. However, they too rushed to the service of their country in 1914. President Poincaré, a conservative nationalist, never failed to express ‘… his thanks for the foi patriotique (patriotic faith) shown by all the organized religions of France and by individual believers.’ (Smith et al, p. 28) Thus he maintained the support of the churches for the war, and they likewise preached in support of the war to their congregations.

Compulsory military service was part of French life and in war time conscription was taken for granted. Compulsion in anything is largely anathema to the British, and for more than a year the number of volunteers was sufficient that it was not required. When it was introduced in January 1916, it contained clauses that allowed conscientious objection, and most of those who objected, did so on religious grounds. By the end of the war there had been 16,000 conscientious objectors, statistically a very small number. Further, most of those who refused to bear arms served in the non-combatant corps or performed some other kind of work in support of the war. (Peace Pledge Union)

Religion had its explanations when God’s Chosen were not winning too. In 1916 during a period of military reverses,

… a Scottish clergyman wrote to the newspapers to say that military failure was due to the fact that, with government sanction, potatoes had been planted on the Sabbath. However, disaster was averted, owing to the fact that the Germans disobeyed all the Ten Commandments, and not only one of them. (Hitchens, pp 183-4)

We can be sure that this view was expressed from many pulpits. In Germany, negative news about the war was rarely reported, but any that filtered through was passed off as a test of devotion or an example of what happened if there was any reversion to excessive materialism. (Hoover, pp 12-14, 67)

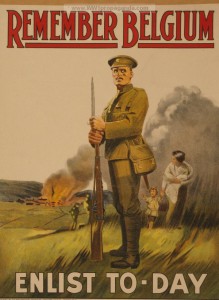

Britain had strong ‘… traditions of liberal individualism and antipathy to strategic involvement on the continent.’ (Stevenson, p. 268) However, churchmen of virtually all denominations were supportive of the war. Britain had not, of course, been invaded, but there was no nobler cause than coming to the defence of ‘Brave Little Belgium’. Brits were left in no doubt by their religious leaders that the conditions of Just War were met for them too. For Germans, this reason was an excuse (to attack the country they were so envious of), a joke (in view of Britain’s history), and completely unjustified. (Hoover, p. 54) The Germans considered that as the state was an instrument of God, and the state considered it a military necessity to occupy Belgium, their actions were therefore justified in the eyes of God. (Hoover, p. 75)

Britain had strong ‘… traditions of liberal individualism and antipathy to strategic involvement on the continent.’ (Stevenson, p. 268) However, churchmen of virtually all denominations were supportive of the war. Britain had not, of course, been invaded, but there was no nobler cause than coming to the defence of ‘Brave Little Belgium’. Brits were left in no doubt by their religious leaders that the conditions of Just War were met for them too. For Germans, this reason was an excuse (to attack the country they were so envious of), a joke (in view of Britain’s history), and completely unjustified. (Hoover, p. 54) The Germans considered that as the state was an instrument of God, and the state considered it a military necessity to occupy Belgium, their actions were therefore justified in the eyes of God. (Hoover, p. 75)

During the First World War, Germany had a deliberate policy of attempting to win the war by political as well as military means. (Fischer, p. 120) Often, this meant religious means. In the Near East, for example, they strongly supported the pan-Islamic movement, principally as a way to open a gulf between Britain and Egypt, but also to put pressure on Russia’s southern border with Turkey. Germany’s commitment to its Turkish-Islamic policy is demonstrated by the appointment of their officer, Liman von Sanders, as commander of the Turkish First Army Corps in 1913. This caused a great deal of tension with Russia, but the Kaiser and his government were not prepared to back down in any way. (Clark, p. 198)

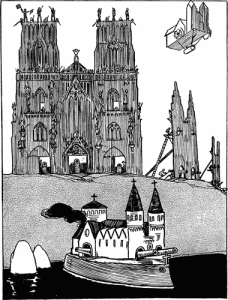

This German propaganda cartoon said the British were cowards – it accused the British of camouflaging military installations, ships, dirigibles etc to look like churches so the Germans wouldn’t attack.

At the beginning of the war, Germany established the Nachrichtenstelle für Auslandsdienst (Information Office for Foreign Countries), the purpose of which was to develop and support external propaganda activities. Already on 2 August 1914, retired foreign minister Freiherr Max von Oppenheim had been recalled as an expert on the Near East. He had gained recognition in 1898 when he had pointed out

… the possibilities of mobilizing the pan-Islamic movement in the interest of Germany’s then embryonic eastern policy. (Fischer, p. 123)

He wrote of the determination of Islam to free itself from the domination of western Christendom, and how a proclamation of jihad

… after the Mohammedan people had been properly prepared, would have incalculable effects. (Fischer, p. 124)

The date of von Oppenheim’s recall is also the date the German-Turkish alliance was concluded, and Turkey’s Sultan-Caliph did, in fact, declare a jihad when they were brought into the war by Germany. (Fischer, p. 122)

While the Germans were giving such strong support to Muslim Turkey, their churches were condemning Britain for

[betraying] the white race when she brought all kinds of coloured soldiers from her colonies to throw against the Germans in the trenches [as] … cannon fodder …. Not only were the enemy troops coloured, they were nearly always pagans and heathens, Hindus or animists. Albion compounded these sins by asking the pagan Hindus … to pray … for victory over Germany.

This was one of the points included in the Address of the German Theologians to the Evangelical Christians Abroad penned by a large group of prominent German theologians in September 1914. (Hoover, p. 56)

In Polish areas, Germany’s propaganda efforts were focused on the Catholic Church, thus they tried to get papal support for their programme. Their line was that Germany wanted largely Catholic Poland independent of the Czar and the Orthodox Church. Thousands of pamphlets were distributed. These showed the Kaiser and Benedict XV side by side against a background of German troops driving back the Russians followed by Poles carrying Church banners and blessed by the Madonna. However, Polish economic interests, and therefore those of the Catholic clergy, were tied up with Russia. The Catholic Church thus used its influence to urge their congregations to support the Western allies, more than nullifying any effects of the German propaganda campaign. (Fischer, pp. 138-141)

The Germans also tried to encourage the Russian Jews,

… to rise to arms, promising them “equal civil rights for all, free exercise of their religion and their civil callings and free choice of residence within any territory occupied in future by the Central Powers”. (Fischer, p. 142)

Support was also sought from the American Jews in this cause. However, due to the high level of anti-Semitism evident in German society, Jewish organizations were naturally skeptical of these promises. The executive committee of the World Zionist Organization, for example, announced a policy of neutrality and forced all their members to resign from the Committee for the Liberation of the Jews of Russia that Germany had sponsored. (Fischer, pp 141-3)

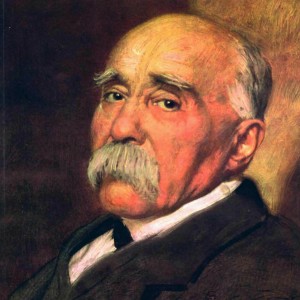

The influence of the churches in all European nations is shown by some of the social consequences of the war. Russia notwithstanding, defeated nations moved to the left, while the victorious ones moved to the right with its military/conservative/religious associations. (Strachan, p. 178) In France, Georges Clemenceau regained power in 1917 and kept it until 1920 (a long time in France at the time). He achieved this because he had popular support from a people constantly lectured on conservative ideals from the pulpit and he successfully managed to brand his opponents as anti-victory. (Strachan, pp 172-3) The recovery of power by the Catholic Church in France is demonstrated by such social policies as managing to have contraception banned shortly after the war. In Britain, the Church’s influence is seen by the attainment of power of David Lloyd George’s conservative-dominated coalition and the policy that separation allowances were paid only to soldier’s wives who remained faithful to their husbands and were ‘conscientious’ mothers. (Strachan, pp 175-7) As in France, Lloyd George was successful ‘… only because public opinion supported him against the House of Commons.’ (Strachan, p. 173)

In Germany, ‘many churchmen seemed to go out of their way to keep the war going.’ (Hoover, p. 120) Following a resolution passed in the Reichstag in July 1917 to seek peace without total victory or annexations, a new political party, the Fatherland Party, emerged. It was joined by many conservative churchmen, but also some more liberal ones. They would only support a peace that took into account the requirements of the war aims movement. (Hoover, p. 120) These included extensive annexations, re-locations of local populations, restriction of the political rights of non-Germans and an expanded German empire. (Fischer pp. 184-279) Prominent and influential theologians such as Adolf von Harnack strongly supported these aims, to the confusion of those who had met him at the Anglo-German peace conferences before the war. (Fischer, pp 172, 276, 604)

Bishop of London Arthur Winnington-Ingram said “The good old British race never did a more Christ-like thing than when, on August 4, 1914, it went to war.” (Hoover, p. 71) Lutheran divine Friedrich König said his country

… had an obligation not to sheathe the sword until a judgment against England had been rendered. (Hoover, p. 55)

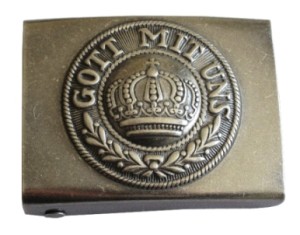

The support for the war by virtually all churches and churchmen meant governments had little pressure on them to negotiate for peace. They were able to borrow money from their people and draft large numbers of workers, including women, into producing arms without reducing the number of men on the battlefield. All countries therefore fought only for victory. (Stevenson, p. 290) Both sides sincerely believed right was on their side, and for most people, that meant God. German soldiers had Gott Mitt Uns (God is with us) on their belt buckles, while civilians were literally starving to death.

Governments in all the belligerents were under intense domestic pressure not to terminate the conflict without achieving their desired objectives. To an extent, they were trapped by their own rhetoric. (Stevenson, p. 292)

The influence of the churches and religion during World War I was significant. All governments relied on them to support their actions and persuade their populations that what they were doing was what the Christian God wanted.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barraclough, Geoffrey, The Origins of Modern Germany. Oxford: Blackwell, 1976.

Clark, Christopher, Kaiser Wilhelm II. Edinburgh: Pearson Education Limited, 2000.

Fischer, Fritz, Germany’s Aims in the First World War. New York: Norton, 1967.

Hitchens, Christopher, The Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the Non-Believer. Philadelphia: Da Capo Press, 2007.

Hoover,AJ, God, Germany, and Britain in the Great War: A Study in Clerical Nationalism. London: Praeger, 1989.

Hüginger, Ganolf, ‘Religion and War in Imperial Germany’, in Anticipating Total War: The German and American Experiences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Jenkins, Julian, ‘War Theology, 1914 and Germany’s Sonderweg: Luther’s Heirs and Patriotism’, The Journal of Religious History, Volume 15, No. 3, June 1989, pages 292-310.

Joll, James and Gordon Martel, The Origins of the First World War (third edition). London: Longman, 2007.

Keegan, John, The First World War. London: Pimlico, 1999.

Marrin, Albert, The Last Crusade: The Church of England in the First World War. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 1974.

Moses, JA, ‘State, War, Revolution and the German Evangelical Church, 1914-18’, The Journal of Religious History, Volume 17, No. 1, June 1992, pages 47-59.

Moses, JA, ‘The British and German Churches and the Perception of War, 1908-1914’, War and Society, Volume 5, No. 1, May 1987, pages 23-44.

Smith, Leonard V; Audoin Rouzeau, Stéphane; Becker, Annette; France and the Great War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Stevenson, David, 1914-1918: The History of the First World War. London: Penguin, 2004.

Strachan, Hew, The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

If you enjoyed reading this, please consider donating a dollar or two to help keep the site going. Thank you.

Thanks for the informative essay Heather. Since the time of Constantine, Christian churches have been more than willing to betray the principles of their founder in the interests of the rich and powerful, including warring states. Many of us hoped that the decline of religion would break this nexus with war profiteers and nationalists. Unfortunately the vitriol coming from so-called atheists such as Jerry Coyne make those hopes seem quixotic. Coyne has shown himself to be a Zionist in atheist clothing, and is agitating for war against Islam as much as any right wing Christian evangelical.

There was no good reason for WWI and the willingness of Christian leaders to make cause with other religions to kill their fellow Christians, demonstrates once again that religion is nothing more than a propaganda machine to serve the interests of the rich and powerful. Millions of poor dupes were led to their deaths by religious leaders serving their own selfish interests. It’s disgusting, but it’s the reality and has been since religion was invented for that very purpose.

Thanks for your comments Paxton.

Many studies of the origins of the First World War describe it as “inevitable”. It saddens me that any war should be considered that way, but this one was, in my opinion, about as avoidable as they come.

There was a scene in Blackadder Goes Forth where the General was standing over a model of the land captured by the British in a particular battle in which many lives were lost – it was about a metre square, and 1:1 scale. It’s a “joke” representative of the whole war.

I find it ironic that in war both sides seem to claim that “God is on their side”.

If you look at religious writing every faith seems to extol the virtues of peace and caring for one’s fellows.

I have yet to see any logic that shows how these two ideologies are compatible.

Human conflict and religious differences seem to be deeply linked in history. As a species we should be able to do better!

Yes. The fact that both sides were using exactly the same religious arguments to exhort their people to greater efforts should have given them pause. But, as always with religion, they just decide that the “others” are wrong. Religion is so often more about dividing people than uniting them.

This was a very interesting article.

Thanks AU 🙂

Pope Benedict XV was a constant force for peace during WWI and maintained a neutral stance. His peace plan was incorporated in US President Wilson’s plan that eventually ended the war.